Stevie Winwood Keeps Traffic Moving

Stevie Winwood Keeps Traffic Moving

New York Times

December 20, 1970

By Albert Goldman

The first time I met Stevie Winwood, pop music's infant Mozart, he was buried under a pile of wriggling groupies. I had gone backstage at the Fillmore during the first American tour of Traffic and when I walked into the group's dressing room, all I could see was girls. Frizzy, Frowsy girls were sitting, kneeling, crawling all over a broken-down ottoman that contained within its bottomest folds this poor little pixie of a boy. Sitting there with his knees up to his eyebrows, Stevie was completely spaced. He didn't even notice the smoldering joint that must have been burning his long white fingers.

Figuring he must be lonely amidst this harem-scarem, I shooed off the nearest girls and started rapping with him. He was terribly pale and anemic looking. When he began telling me about his boyhood in England and his basement apartment in Birmingham, I suddenly had a flash of him growing up like a mushroom in a coal mine- this little, tender, white creature with his vacant eyes, whispery voice and crazy obsession with music.

All he had done for years was listen to Ray Charles records. He liked to imagine himself a poor, blind black man crying out of his darkness to the world. That was exactly the sound he caught on his early hits, cut with the Spencer Davis band six years ago when he was only 16. Those records-"I'm a Man," "Can't Get Enough of It," "Gimme Some Lovin'"-were tarpits. Each side was a fuming attar of blackness. Stevie would take the lurid organ of the Harlem showbar and back it with a clanking, Afro-Cuban cowbell. When the tune was rocking like the Bethel Baptist Church, he'd start to wail in an illeterate, heart-breakingly naive voice. The lyrics were verbal rags, simple little tags repeated over and over again while a chorus of A-men girls did high spooky things around his head.

When the Spencer Davis Group broke up in 1967, Stevie abandoned his black-on-black style. He had gone as far as he could go in that direction and the new sound of the day was the psychedelic satins of "Sgt. Pepper." Picking up a couple of other Birmingham boys, Jim Capaldi and Chris Wood, Stevie formed a new band named Traffic (the idea was to "keep music moving"). The boys holed up in a remote cottage in Berkshire and jammed all night on the heath like warlocks. Within a couple of months they had written a new bag of tunes and recorded "Mr. Fantasy," one of the dozen greatest albums in the history of rock.

Stevie used this new group like a musical kaleidoscope. He slotted together dozens of plastic-bright bits of music in a constantly flashing colorama. Side one began with a Dayglo calliope ("Paper Sun") followed by a Georgia O'Keefe desert painting ("The Dealer") succeeded by a psychedelic hornpipe ("Heaven Is in Your Mind") ending with a brilliant rock hymn ("Colored Rain") that soared up and up in a characteristic vocal release that revealed how far Stevie had come from the clenched and tortured tones of Ray Charles.

Traffic should have been an enormous success; instead, it was a nearly disastrous failure. The boys couldn't get along (especially after Dave Mason joined them); their music never sounded right outside the studio; and Stevie couldn't bring himself to play the leader. The result was that Traffic's first American tour was called off before it got fairly under way. Chris Blackwell, Stevie's indulgent manager, told him that he would ruin his reputation by touring with such a raggedy band.

That was the winter of 1968, when the success of Cream had everybody talking about "supergroups." Stevie was recruited that spring for a heavily-hyped organization called Blind Faith, which included two rock stars, Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker, and one rock clod, Rick Gretch. The promoters were so eager to market the band that they never allowed them time enough to get together. Blind Faith was tossed into Hyde Park to give a 'public rehearsal" (which drew 150,000 people); then they were locked up in a London recording studio to turn out in a single week, working every day from midnight to 9 AM., a hit album. I watched them one night through the aquarium window of the control booth. They worked in total darkness and tried for a sound like a cool, mysterious underground river. They wanted to trace sensitively oriental patterns and trip out to Marrakesh. When they got to the States, however, they found themselves booked into huge arenas like Madison Square Garden, where the high school apes play tag with the cops and the high point of the evening is a Gene Krupa drum rave-up. Ginger Baker thrives on such a scene; Stevie looked as if he was ready to puke. By the end of the 20-city million-dollar tour, the Blind were barely speaking to each other.

The recently reconstituted Traffic has overcome the problems of the original organization and gone on to realize a unique ideal by becoming the first chamber rock ensemble. Holding down the level of noise and hysteria, playing with real care for tonal values, Traffic offers evenings of beautifully stated music, with every performance a finished piece of work of the sort you'd like to take home for future delectation. (Which is exactly what the fans will soon be able to do. After the success of the group's recent studio album, "John Barleycorn Must Die," it was decided that its next album should be live. During the recent performances at the Fillmore, a huge studio van stood outside the stage door reeling in the music for a release date around the first of the year.)

When I met Stevie Winwood again the other night-across a plate of bagels ad lox at Ratner's-he seemed absolutely unchanged. Sitting there in a plum suede jacket with a Gauloise Caporal fuming between his finely articulated fingers, he smiled enigmaticaly and answered my questions in sentences of approximately one syllable. He had jammed the night before with the Grateful Dead and found them "effective." He wasn't concerned about the current pop let-down because music is "infinite." He thought that the acid scene was falling into "perspective." He considered the ideal creative condition that in which "everything affects you without you thinking about it." Basically, however, he was leaving the talking to his "word man," drummer and lyricist Jim Capaldi.

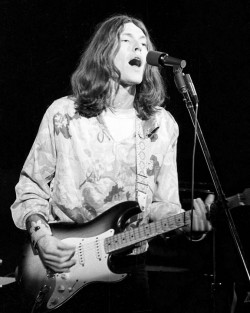

A half hour later, Winwood was onstage at the Fillmore moving from electric guitar to acoustic guitar to electric piano to electric organ in a remarkably cool and self-effacing display of instrumental virtuosity. Sitting there in the murk of the theater, closing my eyes to the banalities of the light show, I found myself gazing at the brilliant pictures in the music. I could see fields of poppies stretching to the horizon. Chemise-clad trollops in a Berlin cabaret. Ancient reapers marching round a haystacked field. A superb and sophisticated exhibit. Best of all were the moments when Stevie threw back his head and let his voice climb step by step, until you could see yet another picture- a homesick eagle seeking the sun.