"Rock's Gentle Aristocrat" Musician, October 1982

"Rock's Gentle Aristocrat" Musician, October 1982

By Timothy White

It is a sentimental journey under a shifting midsummer sky, the grey and yellow quilts of clouds that hover above the English countryside showing neither approval nor disapproval; properly they evince a benign, atmospheric British frown. Driving expectantly through Berkshire, briefly cruising along parallel with the bright red pleasure barges slipping down the narrow upper reaches of the ancient Thames, the car is throttled past the riverside hideaway in Pangbourne where a certain Jimmy Page once lived (three doors down from the local pub) during the early 70s. Swinging onto the winding two lane thoroughfare leading into the village of Wallingford, the roadside attractions along the route evolve in a gentle blur from unassuming dry good stores and vegetable stalls to genteel shops selling fine riding apparel and oufitttings for the hunt. Not too distant from here, of course, is Lambourne, home of the Queen's stables and paddocks, where her mounts are trained.

Bursting out of the town square, one finds oneself poised upon a sloping ride overlooking the breath-stealing Berkshire downs, acre after prime acre of flowing farming, riding and hunting lands stretched out in all directions. It's a sight to tranquilize the peasant's soul and to fire the poet's imaginations. And the grand, sweeping patchwork with its undulating emerald and gold waves of thriving wheat, potatoes, asparagus and barleycorn - especially barleycorn - heralds the proximity of a humble repository of rock 'n' roll mythology, the quaint cottage to which Jim Capaldi, Dave Mason, Chris Wood and Steve Winwood retreated in 1967 to sow and harvest the first seeds of Traffic's musical legacy.

This is the land of "Berkshire Poppies" and "Coloured Rain", where heaven was ever in the lads' sometimes hash- and acid-addled minds, as they tripped down to a pub in tiny Aston-Tirrold called the Boot to shoot the breeze about Mr Fantasy, the Pearly Queen, 40,000 headmen and fellows with no face, no name, and no number.

"It was some house, some era," Capaldi now recalls fondly. "The rented cottage was our permanent address for 2 years, and then it became a jam center for us and all our heavyweight space cadet companions, like Denny Laine and Ginger Baker. We always had a running battle going with the gamekeeper. He looked after the property for the laird, William Pigot Browne, a friend of Chris Blackwell, the head of our label, Island bloody Records! The gamekeeper used to put big sticks with nails in them across the roads to foil our jeeps and keep us off the damned property. "Some heavy numbers went down there, for sure; a friend on acid flying off the roof of a mini-van as it headed down the driveway into the path of William Pigot Browne, the poor tripper waking up the next day in the hospital with a broken collar-bone; the band recording hundreds of tapes outdoors, many of them filled with birds tweeting wildly in the background so you could scarcely hear what the devil we'd been aiming for; tough Teddy Boy gangs coming 'round occasionally to break in; Joe Cocker & the Grease Band taking over the cottage down by the last bend, joining in the festivities as only they could. Indeed, quite an era ..."

It's not much further now, just past the fork that leads either to Aston-Tirrold, or to the small bustling granary beyond which squats the gamekeeper's house, a scarecrow with a white tin pail for a head swaying in his garden. up the tire rutted chalk road and there, in the center of a copse of hazelnut and pine trees, is a two-story wisteria-draped white brick dwelling with a slate roof and squat red chimney, the song-immortalized "House For Everyone":

My bed is full of candy floss

The house is made of cheese

It's lit by lots of glowworms

If I'm wrong correct me please

The village is a pop-up book

The people wooden dolls

The roads are made from treacle

Think it's time that I moved on

"Listen, I'm not claiming everything we wrote and recorded back in that time was fabulous," says Capaldi. "Many things backfired or we were off the mark. But I sometimes look back and feel that we were an experimental group that went out into the natural wilds just to sort of hammer it all out. Back then, all the rock music was anchored to the city life. The fact that the four of us - all country boys from the Midlands to begin with - went back out to the country to abandon the urban distractions and get into the music set a definite trend."

Many miles deeper into the countryside, outside a lovely manor house, "dating back to the Doomsday Book," according to its rock star owner, and nestled in the vicinity of Highgrove, official residence of the Prince and Princess of Wales, Steve Winwood sips a cup of tea in a typically English garden and cements his colleague's point.

"There was a justification then for moving to the countryside to make music," says Winwood, attired in well-worn jeans, checkered flannel shirt and leather walking shoes. "It was the peace, information and satisfaction you get from actually hearing yourself thinking out loud."

From inside the house, in the recesses of the kitchen, comes an inadvertent rejoinder. "Too true! While you see a sandwich, take it!" booms Capaldi, cracking a joke at the expense of the title of Winwood's runaway hit single of 1981, "While You See a Chance". A house-guest helping himself to a portion of the batch of fresh egg salad on cracked wheat sandwiches prepared by Winwood's wife Nicole, Jim has arrived to cut an album in his buddy's bucolic home-recording center, just as Steve has completed Talking Back to the Night, the followup to the surprise chart-busting LP of last year, Arc of a Diver.

Steve's gleeful laughter shatters the pastoral concord. "Okay," he giggles. "Let's go inside and talk about bloody rock 'n' roll."

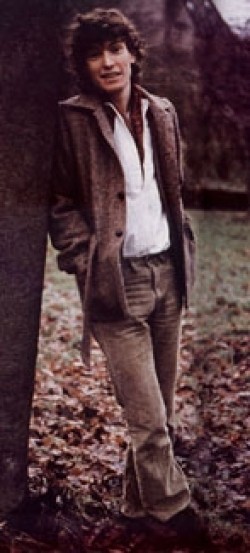

Winwood is slight and small-boned, with smooth pink skin just this side of translucent, and when he walks it's with the puckish, bopping lope of a man perpetually, unabashedly, preoccupied with his own errant muse. His voice is soft yet sharply reedy, and in conversation he punctuates strongly felt points with trembling emotion, which begins as a flush of the angular face, and then slowly builds into an impossibly small hand gesture, a flick of the fingers upon his temples or a determined tapping upon his own wrist. However minute, these actions and reactions can be curiously moving to behold, coming as they do from a man rarely given to hastiness and unsusceptible to the fleeting impulse. A singular presence, Steve Winwood's taciturn, quietly smiling manner combines the spectral aura of a David Bowie with the awesome hunger for life that smolders within and illuminates the delicate, resolute central characters in Dickens' novels. Say, a David Copperfield.

It's all in his eyes: burning, unblinking, fearless, when everything else around him seems sadly timid.

A country gentleman residing in his dream house in Gloucestershire for a decade, Steve Winwood was born on May 12, 1948, in Birmingham, England, and well-nigh weaned on rock 'n' roll, making a living at the craft when most prospective candidates from the provinces wouldn't know a riff from a rafter. Famous by age 16, he's been praised and panned, celebrated and nearly eulogized in the years since. While assured of a place in the rock 'n' roll Hall of Fame, he was almost dismissed as a lifeless trophy on 2 legs before he strode seemingly out of nowhere to reaffirm his status as one of the most original and sagacious talents in the music industry.

But as we should have learned long before now, 34-year-old Steve Winwood couldn't possibly come out of nowhere to do great things.

"He's been on Island Records for 18 years," says Chris Blackwell with pride, "and the album he's just completed will, I think, come to be judged as his best work yet. After all he's accomplished, all he represents in his totally unassuming way, I think that's amazing. The week in 1964 that I signed him, I was up in Birmingham with Millie Small ("My Boy Lollipop") for a TV date, Thank Your Lucky Stars, and I squeezed in time to catch 2 local bands I'd been tipped about. One was called Carl Wayne & the Vikings, which later became the Move, and the other was the Spencer Davis Group. I passed on the first, which was a good group but not to my taste, and signed the second because they had a kid out front who could sing like Ray Charles while still sounding like himself; quite an achievement.

"But that's not what makes him so wonderful for me. And I can only explain that with a little story. Back in 1965, when I managed the Spencer Davis Group and they were on tour in Norway and a very hot band worldwide, this guy talked Steve and me into accompanying him through miles and miles of snowdrifts, to what he had billed as this fantastic party. When we got there, there was only me, Steve, a cheap tinny record player, half a bottle of whiskey - which was illegal in Norway - and forty too-young girls who wouldn't let this 17-year-old rock star leave. And we couldn't understand a word they said. No wonder there are so many suicides.

"It was a total washout. At the end of the night, when we finally talked someone into taking us for the incredibly long journey back to our hotel, Steve turned to me, smiled that schoolboy's grin of his, and shrugged good-naturedly, as if to say, 'No problem.'

"I swear to you, if that happened to us again tomorrow, he'd show the same sweetness, control, strange innocence.

"In spite of all his ordeals, he's completely unjaded. That's what makes him Steve Winwood. And that's why he's a success. All over again.

Musician: You've been at the rock 'n' roll game for a remarkably long time, since before your teens if I'm not mistaken, yet I've never read anything about your home environment as a boy; how were you raised and what your parents were like.

Steve Winwood: That's 'cause nobody's asked me. I grew up on ... a pleasant tree-lined street in a suburb of Birmingham called Great Barr. It was a small house, with a piano in the parlor. The whole family was musical on both sides, with my mother's father being a church organist who could also play flute, fiddle, tin whistle. Same with my dad's people. We'd have musical parties at Christmas, playing folk songs. My father's a very sensible man, a very hard-working man - and strict. Neither he nor my mother nor even my grandparents ever drank or smoked. As a result I think I was much better brought up than most of my friends.

Frankly, a big part of my development was the Boy Scouts; I was both a Cub and a Boy Scout, with the 236th Perry Barr Troop. The Scouts are a fantastic movement. I was reading in the paper the other day where some idiots are trying to get rid of the Boy Scouts, saying that a brilliant man like Baden Powell, the founder, had created nothing more than a sort of fascist youth movement. I was absolutely incensed! I loved the time I spent in the Scouts, camping and hiking in Plymouth, Devon, Cornwall, sometimes up north to Cumberland; and doing bob-a-job: working at odd jobs in the community for a shilling. Got a lot out of it; I went straight from the Boy Scouts into rock 'n' roll (laughter). Fancy that!

As for parental guidance, my father was not the sort of fellow to sit me down and give me a lot of heavy advice but both he and my mother were very helpful in terms of overall support and encouragement. My dad was the manager of Hall's Iron Foundry in Birmingham, laboring in the same profession as his father, and he would have liked me to carry that on, but exerted no pressures. On the contrary, he taught me a few tricks about being a working musician. He played a variety of instruments, mainly sax, bass, and drums, and led various bands, but he used to advertise for his own group as if they were two different bands, one very expensive and snobbish, and the other very working class and cheap. One way or another, he always got work. Pretty shrewd, I thought.

So he endorsed your musical ambitions?

Very much so. But you must be aware that rock 'n' roll is not now nor ever has been considered real music in Britain. Please don't take this lightly; this is a crucial point for anyone trying to understand the outlook and perspective of an aspiring popular musician in this country. Ours is a very stratified, disdainful social structure in which anything produced after the days of Elgar and Vaughan Williams is not considered to be on any value whatsoever. It isn't considered, period. And I'm not exaggerating. I was kicked out of Great Barr Comprehensive School at age 16 because of my 'unsavory activities' with the Spencer Davis Group. A warning came at a school assembly, where it was announced publicly that 'certain students' in the school were known to be connected with untoward musical companions.

Soon afterwards the headmaster, one Oswald Beynon, summoned me to his office for a one-sided discussion. I stood before him in my uniform of grey slacks, black blazer with the school crest on the pocket, and green, white and black striped tie, and he sacked me on the spot for playing rock 'n' roll. Being 16, my attitude was, "Well, screw you too, geezer!" But what was most important was that my father and mother backed me up and were not upset that I'd been kicked out. They regarded the whole matter as being thoroughly ridiculous, which I've always deeply appreciated.

Well, you've taken some hard knocks and been handed some raw deals in your post-Great Barr Comprehensive School experiences. It's not generally known, but you nearly died from a bout with peritonitis during the period ('72-'73) that you were touring and recording Shootout In(sic) The Fantasy Factory.

True. That was when I was writing songs like 'Sometimes I Feel So Uninspired'. That song reflected a lot of things; the state of the rock 'n' roll world at that point, my own frame of mind, struggle with my health. It was just an honest thing; the song was talking about a definite sometime-feeling I get. We can't be inspired all the time, can we? And those of us who are made to feel that we have to be, grow weary and even ill from the stress of the crazy, unfair responsibility put on us.

My peritonitis started as appendicitis and what happens is that these poisons spread throughout your entire body and you virtually fill up with toxins. I was desperately ill, trying to keep touring and functioning, and my condition was such that it wasn't until I'd gone through several doctors, various trips to the hospital and exploratory surgery that they figured out I was in a most delicate and serious state. Peritonitis, by the way, is what killed Houdini. My recovery was slow and painful. A terrible, terrible thing for me. One of the toughest times of my life - but by no means the only one.

Hmmmm. Makes me reluctant to ask what the others might have been.

Well, disbanding Traffic in 1974 was difficult, of course. But the period between the completion of the long-promised - or threatened - Steve Winwood solo LP in the spring of 1977 and the release of Arc of a Diver in 1981 was quite hard for me professionally. The music industry went through such a strange stretch in 1977, especially in this country, with the whole punk rock thing coming about. Punk was rebellious - and justified in that response - but it had very little to do with music and so it created a highly-charged but frighteningly floundering atmosphere that I found very, very disheartening. Musical quality for me has always been an important part of rock 'n' roll - and winning recognition for that has been an uphill battle all the way. Punk seemed like rock 'n' roll utterly without the music.

Did you also suddenly feel as if there was no audience receptive to your reemergence? That your music had suddenly become anachronistic in the marketplace?

Not really; I was concentrating less on the marketplace than on myself. I realized that if I was going to carry on in this business, then 1977 was the beginning of my ultimate trial, but rather than let that burden lay too heavily on me, I decided that the creation of the sequel to the first solo record was the key objective. My career needed new continuity. Also, at that time I was going through some writing problems as well. Capaldi, who was the only person I'd ever written with, in terms of a true ongoing partnerships, had moved away to Brazil for tax reasons. I has no lyricist I could rely on, and no band. In the days of Traffic and the Spencer Davis Group, there was always a group requiring new things to play, so I'd somehow dig in with a collaborator like Jimmy Miller or Capaldi and get it done.

It's funny though, because in this case as well as others, the really bad periods for me have tended to be rather good periods after a while. It's the bad periods that were the times of realizations and gestation which made possible the resurgence.

If you were so hard up for collaborators, why didn't you simply follow Capaldi to Brazil?

Well, because I couldn't put a price on not living where I wanted to live. I was too selfish. I was willing to pay the disastrously dear price of giving 95 per cent of what I earned to the British government in order to stay where I was. It was pretty decadent of me, when you think about it, and pretty stupid too. Thank God, things aren't so bad now with the Thatcher government.

I'll tell you straight: the pressures on me were huge. I was quite literally running out of money. Following the Steve Winwood record, which I cowrote with Capaldi and Viv Stanshall, I knew I was looking at my last shot to stay in the business. If the next album wasn't at least mildly successful, I would have had to leave the record industry because I simply couldn't afford to be in it any longer. I would have had to undergo some drastic professional and personal lifestyle changes.

Are you saying that, with the lack of significant sales of the first solo album and the second looming before you, Steve Winwood was considering quitting as a performer?

Quite possibly, yes. I knew I was going to run out of cash and resources soon, and I was thinking about exploring other areas, perhaps getting a job with a record company as a producer. My brother Muff is head of A&R at CBS in England. I'd considered and tried sheep farming, cattle farming, all kinds of alternate ways of making a living. But I quickly realized that all the mistakes I'd made in the record business over the years were very valuable, that I'd paid my dues and, for better or worse, staked out my territory in terms of competence.

So you literally approached Arc of a Diver as a make-or-break project?

(nodding grimly) But I suppose I still refused to believe that the strain from such a situation is what maybe makes a successful album. I expected absolutely nothing from Arc of a Diver. Nothing. And I thought, "I'm just going to make a record and then I shall settle up financially, and move, if necessary, to a small flat or join a gypsy caravan." I figured I'd continue doing some things that I like doing and enjoy life as best I could in diminished circumstances.

You almost had to give up this house?

Oh, sure. And I would have done that easily, although there was almost no two ways about it. I was going to be forced to.

Must have been pretty scary.

See, now this is the thing: when it gets right down to it, it's not scary at all. I would have managed to have a gentle, peaceful life, somehow. You don't have to have a big house and a lot of land to have a peaceful life. You can create it in other ways.

But, as I say, although that was such a low point, it was a good juncture too because I came to a lot of realizations about myself and about materialism. It was just material things that I was really worried about. I figured that I could do without them, and I was able to take a lot of the load off myself. If I'd have been making a record feeling, "This has got to be a hit," there would have been no hope at all. These were the kinds of things that were on my mind, I can tell you, when I wrote "While You See a Chance."

You also seemed to be attempting to minimize the heat you were feeling artistically by billing Arc of a Diver, on the inner sleeve, as 'an album of songs by Will Jennings, George Fleming and Viv Stanshall.' How did you come to take your perilous last plunge in that company?

Just from needing to find lyricists. I was working with a lot of different ones, and that proved to be good because it taught me a lot about songwriting. Talking Back to the Night is the first time that I've actually sat down calmly and written songs. Right now, I'm in the position where I truly want to write so much, but I don't seem to have the time, basically due to the fact that I'm now making records in this solitary and very time-consuming fashion.

On the new record, Will Jennings basically wrote the lyrics and I wrote the music but there was a bit of a dynamic collaborative overlap too. I have not written a lot of songs by myself, mind you. The first song I ever wrote, at the age of 12, was "It Hurts Me So", which the Spencer Davis Group recorded several years later. I wrote "Empty Pages" by myself for Traffic, with a bit of help from Capaldi; I wrote "Had To Cry Today", "Sea of Joy", and "Can't Find My Way Home" for Blind Faith, and I wrote "Two Way Stretch", the B-side of "There's a River", which is on the new album but which came out first as a Christmas single in 1981.

Those early Spencer Davis Group hits you wrote with Jimmy Miller, like "I'm a Man", how did those come about?

Jimmy was brought in by Chris Blackwell to produce the Spencer Davis Group, and we just knocked around in the studio. We'd all write and cut 3 or 4 songs in a day's work. Back then, if you only completed 2 tunes in a single session, you were screwing off. As for Chris, I met him in 1964 at Digbeth Civic Hall in Birmingham, which has always been a big center for Jamaicans in England; they used to hold their dances there, and naturally Chris was in on the ground floor in terms of Jamaican ska and rocksteady. Business-wise, he and Island were the ground floor.

Anyhow, I'd been playing at Digbeth since I was 14 with the Muff Woody Jazz Band, my brother's group. And that was where I met Spencer Davis, too. But my own Jamaican connection goes back to Digbeth Hall in 1961, when I jammed there with Rico, the trombonist who had worked with the Skatalites and all the other great early Jamaican acts. I was just 13 but I used to go there and play with Owen Grey, Tony Washington, and Wilfred "Jackie" Edwards. Jackie, you'll recall, wrote the Spencer Davis Group's first number 1 hit in England, "Keep on Running", and a followup, "Somebody Help Me". I wrote "When I Come Home" with him for the group.

You've worked in the studio with a lot of very different people: Stomu Yamashta and Michael Shrieve, the Fania All-Stars, Marianne Faithfull, Sandy Denny, Toots & the Maytals, George Harrison, Mike Oldfield, even Hendrix, playing the organ on "Voodoo Child". But there must have been some unheralded live backup work in the early days, when the Spencer Davis Group and the early Yardbirds were doing gigs at haunts like the legendary Crawdaddy in Richmond, Surrey.

Sure! I did backups for Sonny Boy Williamson - as everybody did - but also for T-Bone Walker, Charlie Foxx, John Lee Hooker, Memphis Slim. John Hammond, too. I met John on a train, while going down from Birmingham to London; this would have been about 1963 and I was 15. He told me he had a gig in Birmingham the next week at the College of Advanced Technology and I showed up and played piano behind him. Those kinds of spontaneous musical meetings were special back then, and definitely helped shape my growth. I also played with Jimmy Page for a solo album of his after he'd left the Yardbirds. The music wasn't heavy like Led Zeppelin, as I recall, it was quite nice.

Who would you say were your biggest influences vocally, apart from Ray Charles?

Just about every blues and R&B singer I heard on the radio as a lad had an effect on me, but particularly people like Garnet Mimms and Jackie Wilson. I used to hang out a lot in a Birmingham record store called the Diskery - which is where Capaldi claims I first met him in 1966 - and I loved to listen to all the great black American singers. I also listened to a lot of skiffle too; Lonnie Donnegan and the rest. Oddly enough, I was not a big record buyer. Back in the 50s, my uncle Alfred, who was a marvelous inventor and electronic wizard who had worked on the design of the Norton motorcycle, constructed a tape recorder from scratch and then gave it to Muff and me. For a home-made model it was fairly good-looking and we used to keep it up in the bedroom we shared. At night we'd stay up and tape everything off the radio. It was much better than a record player, really, and owning a tape recorder at that time was quite a novelty. Before long, we had a wonderful collection of tapes of Fats Domino, Louis Jordan, Ray Charles, you name it.

I can hear all of those people threaded through your own work, but one thing I've always been curious about was the integration of the Hammond organ into your sound. How did that come about?

It was accidental, actually. I got into playing the organ because the Place, this club in Stoke-on-Trent that the Spencer Davis group used to appear at, has a Hammond organ there as a fixture for use by the various acts. It was the type of place that would feature a Cabaret Night on a Thursday and a Rock 'n' Roll Night on a Friday, and I had the opportunity to fiddle around on the organ, instead of the usual piano. I just grew to love the large, swelling sound.

Frankly, I'm not that good a piano player. Elton John is much more accomplished on the piano; it's a percussion instrument and he knows how to get the most from it in terms of figures, chording and live performing. But I don't think he's as good an electric piano, organ or synthesizer player as I am.

The difference between piano and the other 3 is vast. You can get expression from organs and synthesizers through pedals but generally not through touch. The feel, the dexterity and the dynamics are arrived at from different directions, but I would argue that the musical possibilities are the same, qualitatively, for percussive keyboards and electronic ones. Yet it is peculiar how the truly fine piano player is frustrated by the technology and the lack of immediate subtlety in organs and synths. Actually, the "touch" is there for the latter, lying beyond the basic key-contact tonality, but you must learn how to find it.

For the last 2 albums I've used a Multimoog for bass and some lead lines, and a Prophet 5, a polysynthesizer made by Sequential Circuits, for most leads on Arc of a Diver. I also used a Steinway piano and a Yamaha CS-80, too, as well as a host of different guitars: an Ovation acoustic, this 1954 Fender Stratocaster, an Ibanez mandolin on a track of Arc of a Diver.

On this last album, I used the Prophet 5 exclusively, which is very limiting; I would never have dreamed that I would have found myself doing that. I just never found the need for any sound I couldn't get out of the Prophet 5. And the Multimoog is where I get the effect that everybody thinks is a saxophone. In terms of drums, I use a Haman kit, with a Ludwig snare, and a Linn Electronics, LM-1 box. Lastly, I use a Roland Vocoder and an ANS Phaser, model DMT20. By using a 16-track machine, you overcome most limitations on the part of the instruments, in addition to several of one's own shortcomings. And with my new-found wealth, I've already ordered a new 24-track custom board.

But one wonders if this one-man show of yours is improving your musicianship?

Well, it's expanding the number of things I can conceptualize in my head - dramatically. Now, people think I play difficult things on piano and organ. My part on "Glad" sounds difficult, but it really isn't. I shouldn't say this, but it's true. When I was very young, I received about 2 years formal training at the Birmingham Midland Institute, studying theory, technique, a bit of the classics, so that gave me a foundation. But I'm not a virtuoso. What I got from the experience was the knowledge that I was never going to be much of a piano player - and that was very valuable. At least I knew then that the way for me was organs and synths. My old teacher's name was John Rust. As Neil Young says, (laughs) "It's better to burn out than to rust!"

How do you overdub your vocals on these solo albums?

I generally put a vocal down fairly early on, and then I do a second one when the track is nearing completion. Usually I end up using the original. I find that in my original there are a lot of deft lines that I patch into the master. I don't keep going until I sing one track that is right all the way through. I've found out at great cost that that's not the intelligent way to use recording equipment.

How do you mean, "at great cost"?

By erasing great performances that contained flaws while working to get one that was absolutely correct! I can't think of any instances where that hasn't happened! I was talking on the phone the other day with Pete Townshend, and he was saying how he always does all these damned demos for himself. I said that I had recently vowed that I was never going to make another demo! You've got to resolve to capture the original spirit. In the old days, you wrote the song, went in and cut it, and that's how it should be. Forget these demos, because when you make them you decide in the first place that it's not going to be any good, that it's just to play for so-and-so who might want to use the song or give you a deal. Why limit the possibilities? It makes no sense! I say, cut every track as if it might be a worldwide smash and then utilize it from there! Chop it up any way you please but use what's good. I've decided to value everything I do - but I must say that the tape gets very expensive.

I did a lot of trial tapes for Talking Back to the Night, recording them at slower speeds to save tape space. I tried to recut them later but said, "Sod it!" and went back to the originals. You've got to forget all preconceptions when you sit down to record and let things happen. Especially when you're working alone. That way surprising things can be allowed to occur.

Give me a recent example of an unexpected moment that was saved for the record.

The ethereal beginning of "While You See a Chance". What happened there was that in the studio, I had record switches for each track that were mounted flush with the board desk, on top of which was habitually piled reams of notes and paperwork.

At one point, I inadvertently knocked a record button on as I went down into the studio to do a vocal. Twenty bars into the song, I suddenly said to Nobby Clarke, my engineering assistant, "I can't hear the bloody drums!" He stopped the tape immediately, and we found that we'd accidentally wiped the drums off the first part of the track - originally they'd come in at the top of the tune. I spent months trying to patch in the drums again, and never got it right. We were getting close to delivery day for the tapes to be mastered, so I just left the drums and vocal out, and reshifted all the verses. It actually made the song. That's how bizarre the recording process is.

You've got to have the ears of an engineer, a producer, an aranger and a composer to pull these new albums off, plus the instincts of an A&R man. Who critiques your daily output?

I do, and Chris Blackwell, plus my wife Nicole, who has very good ears, and can be quite demanding, in a kindly way.

She also has a powerful voice, judging from her backing vocals on the new single, "Still In the Game." But don't you ever get lonesome for the companionship of other musicians in the studio?

Sometimes. Other times I'm too wrapped up in what problems I'm solving and what discoveries I'm making to be awfully concerned. Also, I save money - which was critical until just recently, you'll recall. And (beaming/blushing) I'm proud of myself.

There's always been a churchlike feel to your playing, something oddly ecclesiastical about your keyboard work, your musical themes and the reverential intonations in your singing. Songs like "Rainmaker", "Sea of Joy", "Can't Find My Way Home", "No Face No Name No Number", "Coloured Rain", Dear Mr Fantasy", "Many a Mile to Freedom", "While You See a Chance", "There's a River" - they all sound like they'd practically be acceptable in an Anglican cathedral. Would you agree?

(grinning) "There's a River" is downright hymn-like, isn't it? Actually, I rather like church music, and to do my part for the local people out here in Gloucestershire, I actually play organ at a nearby church on the average of twice a month. As a boy, I sang in choir back at St John's, Perry Barr. Used to get into a bit of mischief back then as well, mucking around behind the altar screen during services, making nasty cracks or horsing around afterward in the vestry and stealing the communion wine. They were good days, not overly reverent.

In terms of my singing, I have always loved to hear the sound of the big voice resonating in my head. It's so thrilling, and never fails to keep me happy. I loved the vibrations and the auras that choral singing brought about in my voice, so I must have gravitated toward that music a bit for that reason alone. The churchlike overtones are definitely there in my music and I would say that that dimension came on naturally and not deliberately. I like that people hear it in there. They're not just imagining it.

Are you religious?

No. Not really. I don't pray. I do feel very strongly about natural law, however, and the importance of people respecting it. That's become a kind of religious conviction for me, but I'm not a conventional churchgoer. I have my philosophical side, but it's not dogmatic.

So where does the spookiness, the prayerlike poignance and the almost aching wistfulness in much of your music stem from?

There is a sense of longing there, perhaps, but I don't analyze it. To touch a listener is great, though. Those moods and emotional shadings are there but I like to think that I'm down-to-earth with them, particularly as of late. As time goes on, I feel more rooted, more grounded. In the early 70s, I was like a lost soul, wondering what the hell I was going to do with my life. And from 1974 to 1977, I did almost nothing except to kick back and get to know people I'd never know before, like farmers, simple tradesmen, and country folk who had no idea who the hell I was.

Interestingly enough, the fact that I wasn't doing much music during those years didn't bother me because, Lord knows, I'd been at it for 12 years by the time Traffic broke up in 1974, just shortly after we'd released When the Eagle Flies. (laughing) I couldn't feel guilty about it when I'd been playing professionally literally since I was in short pants!

Are the royalties from your early work substantial?

Well, the royalties from "Gimme Some Lovin" and from most of the various Traffic records are. As I said before, I've been pressed for money in the recent past, but I don't want to make it sound as if I was almost completely down-and-out.

What was the best-selling Traffic record, to the best of your knowledge?

I think it was Low Spark. Not John Barleycorn, as some believe. Barleycorn came after the breakup of Blind Faith in the early 70s. I'd knocked around a bit with Ginger Baker's Air Force an then I was supposed to do my solo album; I was going to call it Mad Shadows. But Capaldi and Chris Wood joined in and it turned into a Traffic album.

"John Barleycorn" is an ancient British folk song with hundreds of versions. How did you come to record it as the title track of a Traffic album?

That goes back to the basis upon which Traffic was formed. The reason I left the Spencer Davis Group in 1967 was because I didn't want to continue playing and singing songs that were derivative of American R&B. I'm sure it's no accident that "I'm a Man" was one of the last things I ever cut with the group. It was a fine record, which we did on the first or second take. It was intended for some sort of Swinging London-type film called The Ghost Goes Gear, or whatever; one of those silly films we were involved with back then. I just believed I had more to offer than that. Also, I wanted to play with younger people, fellows my own age. I was 15 when I joined up with Spencer, Muff and Peter York. They were all a bit older than me, with different musical orientations.

I'd begun to make younger friends like Dave Mason, who was working for Spencer Davis as a roadie, and Capaldi, who was the lead singer in a group I'd jammed with called Deep Feeling. And I sang some blues stuff briefly with Eric Clapton, Jack Bruce on bass, Paul Jones played harp, and so on; we were called the Powerhouse. When Jim, Dave, Chris Wood and I went up to the Berkshire Cottage in 1967 to start Traffic, it was the result of a lot of enthusiastic planning and time spent playing together informally. What came out of those talks and things was a desire on the part of the 4 of us to make a uniquely British form of rock 'n' roll that incorporated or evoked traditional music like "John Barleycorn" - the Berkshire cottage was in the center of acres of wheat and barley - while breaking new ground artistically.

Are you saying that there was no determination collectively to turn out a variation on the psychedelic rock then gaining ground commercially?

No, no! Absolutely not. We would smoke our share of pot and hash and so forth but that was never on our minds in any specific way when we wrote songs. We were trying to keep the images in the music clear and simple, not complex and cerebral. We were hippies of a sort, I guess, and those were heady times; a whole era - sitting in with a colorful, nervous, lovely bloke like Hendrix in a Greenwich Village studio, or brain-storming in the Berkshire cottage with Traffic - that was filled with a vast, unfounded kind of pleasure at tearing down any and all barriers. I'm not sure why, now, because if you destroy too much you're just left with a gigantic mush, which is kind of what happened a bit, isn't it?

And then again, Traffic can't take credit for removing barriers as much as others because we were so keen to work in established areas of folk and folk-rock music.

Did you believe at the time that you were getting anything concrete out of your hash-smoking reveries in the cottage?

I thought I was getting something from it, yes, but I've since realized I got nothing whatever from it. I see myself as having been misled. The whole notion of reaching another consciousness through the smoke was a lot of crap. But I've few regrets. There're probably little batches of songs here and there during the period which, with hindsight, I should not have released or put out in their now permanent form, but to be very honest, I figured, "What the hell! Put it out, sod it." It's not all great, but, I mean, how often is anything great?

The way you record now, so meticulously, at your own pace and on your own terms, the temptation to go back and tinker with your old material must be enormous.

Oh, you don't know! You can't imagine! Especially in light of all I've learned about the studio. But I don't want to drive myself batty over it. The answer is, "Yes, certainly. But I'd have to be crazy."

The cover of When the Eagle Flies, Traffic's swan song, was as bleak and funereal as the music within. Was that a reflection of a collective state of mind?

Yes. It just kind of turned out that way; it doesn't seem like a Traffic record so much, does it? The whole record is very doomy, and I suppose it's the way we saw both Traffic and the music of the era going. It was an extension of "Sometimes I Feel So Uninspired". The kind of depression that comes from endings and ultimatums, and the title of the album reflects that was well.

What occasioned the demise of the band? On precisely what day did it fold?

If there was a single, final moment I can't recall it now. We'd broken up so many times previously, with Dave Mason leaving and coming back, the Blind Faith sideline after the first 3 Traffic albums, and us constantly adding new players like Rick Grech, Rebop, Roger Hawkins. But I shed no tears. On the contrary, I felt a great relief. Same with my Spencer Davis exit. As I left I felt very cold and callous about the action and much excitement about the future.

You're been quoted as saying you "walked out" on them.

I can't deny that. But what I was trying to convey was that it was time for all of us to disperse. I don't know of any hard feelings between any of us.

Is it true that in the summer of 1976, just before you began the first solo album, you'd seen graffiti around London that read: 'Steve Winwood Lives!" And that it rattled you considerably, as if the public actually had given you up for dead?

It was weird, except that I knew who was responsible. It was this bloke who was trying to become my manager. That was his idea of creating new excitement about me. I had friends who'd seen it in Kensington and 'round the side of Harrods and told me about it. So this bloke eventually came to me and said, "See what I can do for you"? I said, "That's what you can do for me? Remind me I'm still breathing?! Thank you very much and move on, you bloody fool!"

Do you have any hobbies or interests that give you a little release from all these musical chores you're locked into?

Well, I do have an absorbing interest in field sports, game birds, hunting, falconing, and coursing - which is hunting with hounds. But I don't like to talk about it much because I fear people might not understand how and why I can enjoy such things.

In 1970 I thought that I would become a vegetarian and I kept on with it for about 6 months, but I had such a craving for meat. So I decided that if I was to go back to eating meat, I must learn how to kill my own, doing it efficiently, humanely, respectfully.

Also, I resolved that I would not hunt for the mere sport of it, or kill more than I could or would definitely eat, to keep the bargain honorable, and I've stuck to it, I'm happy to say. It seems to have more integrity to me than going to the market to buy a fowl, like most people, yet not facing up to the reality of the situation. Also, things like falconing and the hunt are commonplace in these parts.

Do you ever ride to the hunt?

I used to have horses, which I gave up. A very good friend of mine works for the hunt, but he doesn't ride. He's more of an organizer of it. I like coursing better, I think. I love the outdoors, hurrying about in the fields, if only for the scenery.

Since 1977, you've been threatening to perform live again with a band. In 1980 you went so far as to say you had a "world tour" in the offing. Same thing in 1981. Obviously, all of these promises have come to naught. I'm not trying to give you a hard time, but do you sincerely want to face the road again, to regain the live vigor you displayed at the beginning of the 1972 Low Spark tour?

(smirking)You're not going to believe me now, whatever I say, are you? But seriously, I've been to a couple of concerts in the last few months - Van Morrison and Marianne Faithfull - and at both of them I stood offstage and thought, "God, I want to do some live stuff!" And in fact, I think the material on Arc of a Diver and Talking Back to the Night would be hot, rousing live material. "While You See a Chance", "Valerie", "Help Me Angel", "Still In the Game", they all have the proper feel to connect with crowds.

You aren't plagued by stage fright, are you?

Stage fright comes out of a feeling like, "Am I really certain I want to be doing this?" That kind of trepidation. Not from thinking, "I can't wait to get out there!" which I've surprised myself by experiencing recently. Perhaps after a few rehearsals I'll feel a bit more shaky, wondering if I look stupid doing this or singing that. But let's say this: my stage fright will probably come further down the line, when it's part and parcel with the physical organization of an agreed-upon set of gigs. I'm not shying away from the sensation of the concert stage so much as reminding myself it's a constant possibility. And I have no secret fear of wide-open arenas or large amounts of people.

The biggest tour you've ever been on was the one that had the least to do with your career - the 1969 UK-USA Blind Faith cavalcade. While I'm not one to belittle the album critically - actually, I've always liked it a lot - the Blind Faith tour was one of the tackiest rock circuses of all time. You opened to a horde of 100,000 in Hyde Park in London in June and proceeded to bend every ear in America near the breaking point for 2 months cross-country. Though it didn't last long, it was a fairly vulgar spectacle, and turned off a lot of people who, understandably, took Clapton, Baker, Grech and yourself seriously. Could that have lastingly soured you on your own personal in-concert presence?

The album stands up very well on its own merits. But the show was vulgar, crude, disgusting. It lacked integrity. There were huge crowds everywhere, full of mindless adulation, mostly due to Eric and Ginger's success with Cream and, to a more modest extent, my own impact. The combination led to a situation where we could have gone on and farted and gotten a massive reaction. That was one of the times I got so uninspired.

The attitude backstage was, "These people think we're great and we better damned well give them something great", but it didn't help. And it wasn't the audience's fault. The blame all rightfully belonged in our laps. We did not sound good live, due to the simple lack of experience being a band. We'd had no natural growth, and it was very evident onstage.

Whose idea was Blind Faith?

Eric and I had known each other for ages and had been saying we must get together sometimes and play in a real, stable band. Since I'd just left Traffic and Eric had canned Cream, we decided that was the time, and we rehearsed for 2 weeks at Eric's house in Surrey. We went in and cut the record, and then toured.

I still say, however, that it's better to have a good record and a bad tour than vice versa. Memories always mellow, but the record lingers on intact. At least the album indicates that we could get on a bit musically. But we had to break up because that was the only way we could get out of the whole mess. And it was a complicated deal, because Eric and Ginger were held by Atlantic, and the deals for each member were struck individually, with Chris Blackwell working a thing out with Ahmet Ertegun for me. Not the best way to form a group. Live and learn.

Are there any lingering miscomprehensions that you think the public has about Steve Winwood that you'd like to set straight?

Yeah! I've read in a number of places, bother books and articles, about Steve Winwood being "a victim of the drugs he ushered in" or "a casualty of the drug scene". When Will Jennings, my writing collaborator, first met me, he thought from all this rubbish in print that I was a junkie, or at any rate had been! Because that's what the writers seemed to be implying.

Over the years, my blood has really gotten up about this crap. I'd be all set to take legal