"Ready, Steady, Go": Melody Maker, April 24, 1976

Steve Winwood, Stomu Yamashta, and Michael Shrieve

tell Steve Lake about their new project, "Go".

Steve Winwood climbs onto a small balcony and peers through the curtain at the keyboard of London's Royal Albert Hall organ. The only time he's ever seen this beast played, he says, was when the Mothers of Invention did "Louie Louie" on it. When was that now, '66? '67? Nobody quite remembers.

"And when did you last play here, Steve?" asks someone else. He looks upward and squints at the flying saucers in the Albert's roof, as if trying to find a date to fit the image. But no. He doesn't remember that either. He laughs, amused at his own vagueness.

But Michael Shrieve, we can be sure, is recalling his personal glories as he struts around the empty auditorium on this warm, mid-week afternoon. Remembering, perhaps, how they danced in the boxes during his solo in "Soul Sacrifice", when Santana played their first British concert as part of CBS's Sounds of the Seventies presentation, six years ago.

Lots of water under the bridge since then. Massive commercial success; a period of flirtation with jazz; and half-hearted attempts to become a Sri Chinmoy convert resulting in a new name, Maltreya Michael Shrieve.

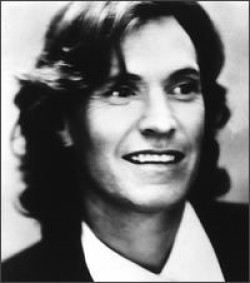

Appearances can be deceptive, admittedly, but Shrieve today looks like a man who has come full circle; everything about him suggests he's ready to rock again.

During the tail-end of his Eastern studies period early last year, complete with cropped hair and discreet moustache he radiated humility, but one would guess that now, newly-permed and tightly denimed, he's itching for a little success again.

He barrels over to where our third VIP, Japanese percussionist Stomu Yamashta is stationed, waiting to pose for photographs. They share a joke. Now they know how many drums it takes to fill the Albert Hall.

Lots more pictures. Shrieve strikes a Leonard Bernstein post on the conductor's podium, arms raised to signify an imaginary crescendo. Flashbulbs pop. Yamashta claims, rather unconvincingly, that the hates having his picture taken. Winwood is obliging, but uninterested in the proceedings.

The very protractedness of it all, however, increases the serious nature of the occasion. Two hours in the Albert Hall, with two managers and a press officer, just for a picture session? Clearly, Island Records mean business this time - as, indeed, they must, for no expense is being spared to ensure that Yamashta's "Go" is a resounding success.

"Go" in this context has nothing to do with Waddington's board games or beat novels by John Clellon Holmes. It's the title of Yamashta's latest epic work, a concept album, an abstract play, a ballet and a stage show all rolled into one. The successor to the excellent "Man from the East" and the rather inferior "Raindog", "Go" is trying very hard to be all things all people, threatening to become, to use one of Cornelius Cardew's more colourful phrases, a king-size multi-media electronic freak-out.

Three ring circuses aren't in it. "Go" combines Stomu Yamashta, Mike Shrieve, Steve Winwood, guitarists Al Dimeola, Bernie Holland, and Pat Thrall, ex Tangerine Dream synthesizer player Klaus Schulze, bassist Rosko Gee, conga players, an orchestra conducted by Paul Buckmaster, Thunder Thighs, a kung fu fight sequence, two gymnasts, two acrobats, a juggler, four dancers, a tiger, a swan, strobes, two banks of TV screens, National Aeronautics and Space Administration movies, multi-beam back projections onto two cinema screens ...

In the studio, as the new album is played back in complete form for the first time, it all begins to make more sense.

Shrieve is in Nietzschean rhapsodies from the outset as a bright Satie-like melody rises from the speakers closely followed by masses of orchestral strings over string synthesizer, ponderous drums and Steve Winwood . . . singing like a blueswailing angel.

The sound of his voice carries the emotional impact of a highly expressive horn player, but here the words, presumably a key insight into the theatrical mysteries of "Go", are unclear. The lyrics, apparently, were written by a mutual friend of parties concerned - one Mike Quartermain.

"Mike had the lyrics all prepared in poetry form," recalls Winwood, "and that's not always the easiest way of writing a song, so some things I took straight, while other things I mutilated to suit the shape of my voice. But, really, it's all Mike's writing; the basic idea behind the meaning of the lyrics is his. Stomu talked the play concept over with Mike, and then he came through with the lyrics."

At his juncture, I reserve judgment on the highly symbolic, apparently philosophical content of "Go" at least until May 29 at the Albert Hall, when, perhaps, new light will be shed upon a couplet like "where the ghost gives up its mind / you can catch the thread of time."

Yamashta, Shrieve, and Winwood clearly understand, but this scribe remains bemused even after thorough scrutiny of the script. Eventually, Yamashta decides that it doesn't matter how the work is interpreted. People can appreciate it on any level they want.

"When you have dancers interpreting the music, you shouldn't need a narrator explaining exactly what is happening. That's a joke. Like the Tubular Bells thing." Yamashta makes a passable stab at a Viv Stanshall impression. " 'And now, Tubular . . . Bells! BOINNNNG!' ..... I mean, can you believe it?"

Shrieve claps his hands. His collaboration with Yamashta, as long-serving MM readers may recall, should have taken place last year. But Shrieve got entangled in the birth throes of a new band, Automatic Man, whose guitarist, Pat Thrall, also plays on the "Go" album.

And meanwhile, Yamashta met Winwood, and proceeded to lock himself away with the entire Traffic, Blind Faith, Spencer Davis, and Santana back catalogue, determined that Mike and Steve were to be featured instrumentalists in his magnum opus.

The announcement that Winwood was to be in the band for the RAH gig and album came as a shock to Shrieve, who counts the man among his favorite singers. Now he's beginning to look upon "Go" as a kind of crash course in personal exorcism.

"This project ties up a lot of loose ends for me. Like, Stevie Winwood had always been one of my heroes; I always hoped that I'd get a chance to work with him some day. And Stomu, well, as you know, I've always wanted to do a gig with him ever since I first saw his photo. Paul Buckmaster is somebody that I've only just recently become really aware of, and having a chance to collaborate with him is just unbelievable. So it seems that this album is like bringing together my past, and when I'm through with it, I'll finally be able to go off and do my own thing."

Buckmaster was actually Yamashta's second choice for arranger. Originally he wanted to get jazzman Mike Gibbs, but Gibbs, because of his teaching work (he's composer-in-residence at Boston's Berkeley School of Music) couldn't make it.

Nobody's complaining about Buckmaster anyhow. Apparently Yamashta sang the parts to him, and Paul got it all down right off, actually extending the composer's ideas in a couple of instances.

Some of the arrangements are exceedingly heavy - much more severe than anything Buckmaster's ever done with Elton John, say. A long sequence which opens the second side, for example, sounds like Mahler with a synthesizer, and is quite terrifying in its intensity.

Shrieve scowls to hear it. "Boy, don't take acid when you're listening to this one," he says to nobody in particular.

This sequence bounces abruptly and unexpectedly into some fine funk, a thing called "Ghost Machine" with more metaphysical lyrics which Winwood manages to make sound entirely unaffected, as much so as "Dimples" even.

These kinds of musical volte-faces occur throughout the work, usually taking the listener very much by surprise. At this stage of the game, it's difficult to see how Klaus Schulze's long synthesizer pieces relate to the album's song content.

Yamashta has no worries, however.

"This album is really only a soundtrack. Y'know, just part of a complete experience. You will understand, I'm sure, when you see the whole show. Some of the parts are written to go with plenty of visual action."

-- Steve Lake